No More Forever

I am from Middle Tennessee, a particular part of that region that has always been on the fringes of history and never in its center. As a boy, I would walk into the field toward the creek and imagine who was there before me. Who owned the land? Who walked on it? Did the soldiers like it here? From a hill down the road at my aunt’s house, I’d imagine seeing fires at dusk in the field near the trees and tipis with people settling in for the night. I once asked someone beside me if they could see it, if they could sense that too. They said no.

Somehow, with no prodding or urging, my imagination was filled with awe at the stories I’d read in school books. I came to love (and hate) what I learned about Native Americans and the interactions with them. One story in particular has never left me.

But first…

I had a standard public school education in a small-ish city. We were not intellectuals. Common people with jobs to do. No grand dreams. Just doing what needed doing to get to the next thing. All the education I received was at school. There were no teaching moments, no wisdom imparted, no sitting down and discussing life. Dad provided for us, mom cared for us, while school and church taught us.

I forget which grade it was, but at some point, we started learning about settlers moving west and coming into contact with natives. The gumption, the drive, the ambition, the courage, and perhaps the desperation (and some greed) was so inspiring to me. There is an energy when someone puts their life on the line, and moving out West seemed like a life-or-death decision even when it came to normally mundane things.

I was a sickly, weak child, and their stories showed me a side of living that made me want to be strong in my convictions if nothing else. Now as an adult, I’m still weak (pale-skinned and allergy-eyed), but the attitudes that shaped the West are still at play, still strong, and form a vital part of the American fabric.

For some, for many, the strength of the settlers and pioneers in their quest for a home or fortune is the definition of what it means to be an American.

It was unfortunate that they were the descending edge of a steamroller’s wheel.

“Unfortunate.”

Here is a story. One of many.

The roaming tribe of what we call Nez Perce (in their language, Niimíipuu - Nee Me Poo - meaning “the people”) lived in bands, welcoming traders and missionaries to a land framed by the rivers, mountains, prairies, and valleys of present-day southeastern Washington, northeastern Oregon, and north central Idaho. They moved throughout the region including parts of what are now Montana, and Wyoming to fish, hunt, and trade.1

The short version:

The part of their home that had become a reservation was shrunk by as much as 90% after the discovery of gold. All Nez Perce wanted to stay, but some decided to leave. An army guy named Howard eventually told them all to move - or else -

and move in 30 days.

Now sad and angry and forced into a new place, a few Nez Perce killed some, maybe 18, settlers. Fearing a war, the leaders of the Nez Perce decided to head north into Montana. Howard followed and fights ensued.

They wanted to escape, not to fight.

Thus began an epic withdrawal - known as

The Flight of the Nez Perce

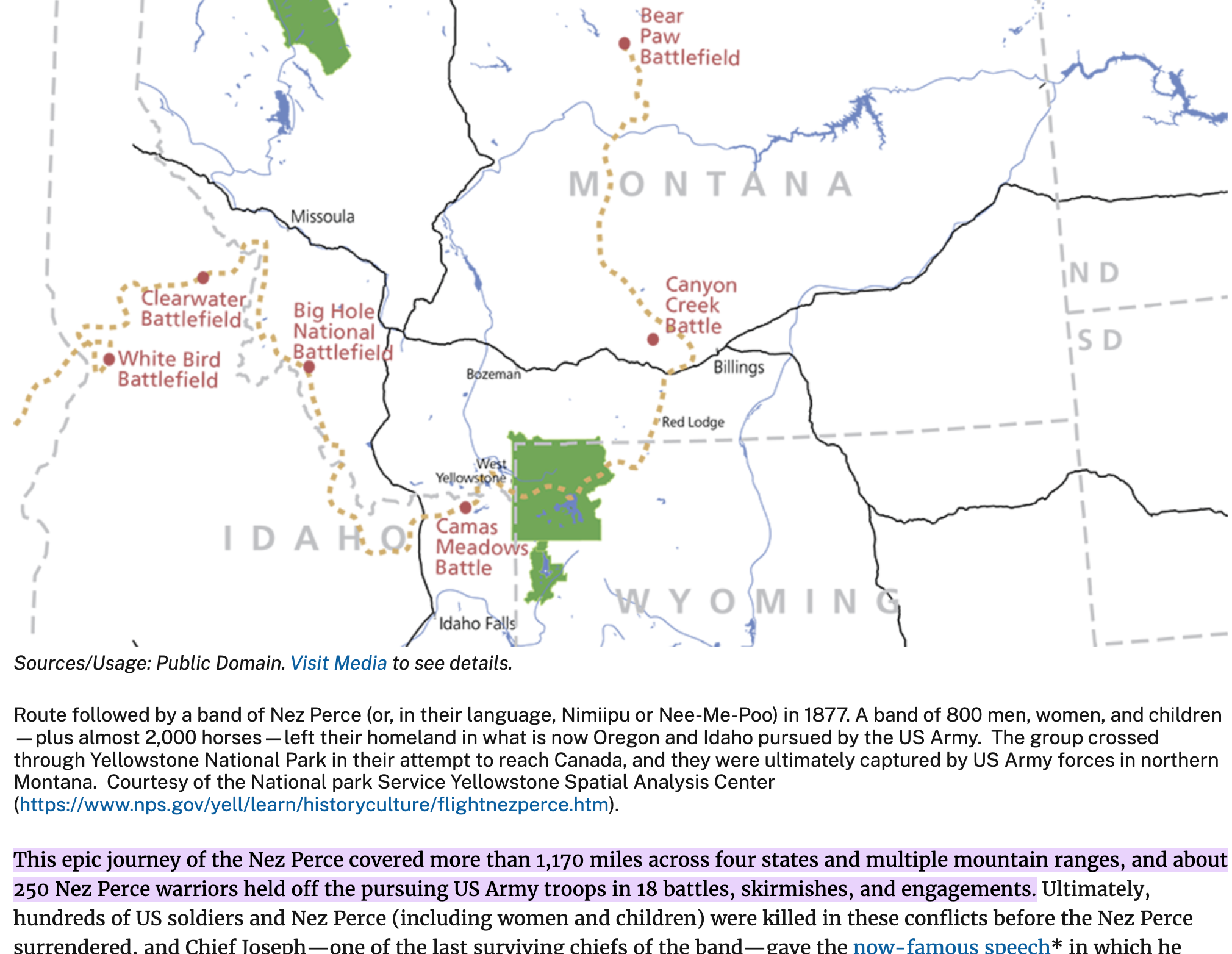

“This epic journey of the Nez Perce covered more than 1,170 miles across four states and multiple mountain ranges, and about 250 Nez Perce warriors held off the pursuing US Army troops in 18 battles, skirmishes, and engagements.”2

Just look how far they went.

Just to escape. Not to escape, regroup, and attack.

Just to get away.

Bear Paw

The Nez Perce, now in northern Montana and only 40 or so miles from Canada,

so close they could basically see it,

outmaneuver General Howard, but their one-time friends, the Crow Indians, began to harass and attack them because the Crow had made peace with the Army.

Exhausted, starving, cold, horse and supply poor - and now in a land without friends -

The leaders of the Nez Perce stop moving to rest and make decisions.

They had left Howard far behind, but had no idea another group of soldiers was speeding to them from another direction.

Northern Montana. Late September. They stop to rest.

Snow falls.

Water and children freeze.

The Army arrives and attacks. Natives defend much better than imagined possible. Native leaders die, but at least one is left. The band leader who had the noble charge of caring for the women and children: Heinmot Tooyalakekt

Chief Joseph.

Before I was 15, I knew his name. I knew how he and his people tried to leave the country to escape the army. His words broke my heart when I first learned them, and they have never left me. I loved him, though I did not know him.

October 5, 1877, Chief Joseph does what he thinks is best for his people and surrenders to the army.

Here is what he said:

"I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Tulhuulhulsuit is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say “Yes” or “No”. He who led the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are, perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever."3

Here, I stop, though their story did not.

I stop and show a small part of a work in progress, which is normally a bad idea, but showing this work in progress, a painting that I am still working on seems appropriate, as there is much work to do. There is much work to do.

It is titled, “No More Forever”